WSTG - Latest

Fingerprint Web Application Framework

| ID |

|---|

| WSTG-INFO-08 |

Summary

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that almost every conceivable idea for a web application has already been put into development. With the vast number of free and open-source software projects that are actively developed and deployed globally, it is very likely that an application security test will encounter a target that is entirely or partly dependent on these well-known applications or frameworks (e.g. WordPress, phpBB, Mediawiki, etc). Knowing the web application components that are being tested helps the testing process significantly and will also drastically reduce the effort required during the test. These well-known web applications have specific HTML headers, cookies, and directory structures that can be enumerated to identify the application. Most web frameworks have several markers in these locations, which can assist an attacker or tester in recognizing them. This is basically what all automatic tools do, they look for a marker from a predefined location and then compare it to the database of known signatures. For better accuracy, several markers are usually used.

Test Objectives

- Fingerprint the components used by the web applications.

How to Test

Black-Box Testing

There are several common locations to consider in order to identify frameworks or components:

- HTTP headers

- Cookies

- HTML source code

- Specific files and folders

- File extensions

- Error messages

HTTP Headers

The most basic form of identifying a web framework is to look at the X-Powered-By field in the HTTP response header. Many tools can be used to fingerprint a target, the simplest one is netcat.

Consider the following HTTP Request-Response:

$ nc 127.0.0.1 80

HEAD / HTTP/1.0

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.0.14

[...]

X-Powered-By: Mono

From the X-Powered-By field, we understand that the web application framework is likely to be Mono. However, although this approach is simple and quick, this methodology doesn’t work in all cases. It is possible to easily disable X-Powered-By header by a proper configuration. There are also several techniques that allow a site to obfuscate HTTP headers (see an example in the Remediation section). In the example above, we can also note that a specific version of nginx is being used to serve the content.

In the same example, the tester could either miss the X-Powered-By header or obtain an answer like the following:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.0.14

Date: Sat, 07 Sep 2013 08:19:15 GMT

Content-Type: text/html;charset=ISO-8859-1

Connection: close

Vary: Accept-Encoding

X-Powered-By: Blood, sweat and tears

Sometimes there are more HTTP headers that point at a certain framework. In the following example, according to the information from HTTP request, one can see that X-Powered-By header contains PHP version. However, the X-Generator header points out the used framework is actually Swiftlet, which helps a penetration tester to expand their attack vectors. When performing fingerprinting, carefully inspect every HTTP header for such leaks.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.4.1

Date: Sat, 07 Sep 2013 09:22:52 GMT

Content-Type: text/html

Connection: keep-alive

Vary: Accept-Encoding

X-Powered-By: PHP/5.4.16-1~dotdeb.1

Expires: Thu, 19 Nov 1981 08:52:00 GMT

Cache-Control: no-store, no-cache, must-revalidate, post-check=0, pre-check=0

Pragma: no-cache

X-Generator: Swiftlet

Cookies

Another similar and somewhat more reliable way to determine the current web framework are framework-specific cookies.

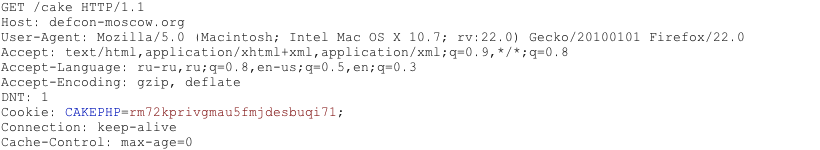

Consider the following HTTP request:

Figure 4.1.8-7: Cakephp HTTP Request

The cookie CAKEPHP has automatically been set, which gives information about the framework being used. A list of common cookie names is presented in Cookies section. Limitations still exist in relying on this identification mechanism - it is possible to change the name of cookies. For example, for the selected CakePHP framework this could be done via the following configuration (excerpt from core.php):

/**

* The name of CakePHP's session cookie.

*

* Note the guidelines for Session names states: "The session name references

* the session id in cookies and URLs. It should contain only alphanumeric

* characters."

* @link https://php.net/session_name

*/

Configure::write('Session.cookie', 'CAKEPHP');

However, these changes are less likely to be made than changes to the X-Powered-By header, making this approach to identification more reliable.

HTML Source Code

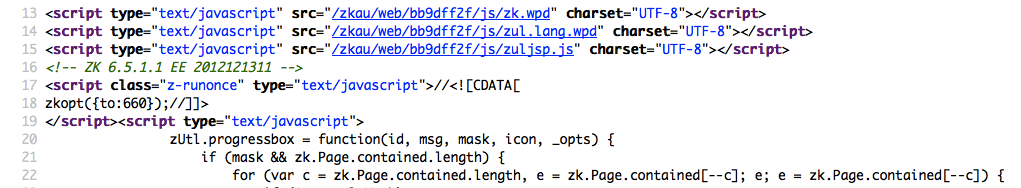

This technique is based on finding certain patterns in the HTML page source code. Often one can find a lot of information which helps a tester to recognize a specific component. One of the common markers is HTML comments that directly lead to framework disclosure. More often, certain framework-specific paths can be found, i.e. links to framework-specific CSS or JS folders. Finally, specific script variables might also point to a certain framework.

From the screenshot below, one can easily determine the framework in use and its version by the mentioned markers. The comment, specific paths and script variables can all help an attacker to quickly determine an instance of ZK framework.

Figure 4.1.8-2: ZK Framework HTML Source Sample

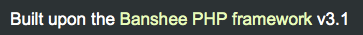

Frequently such information is positioned in the <head> section of HTTP responses, in <meta> tags, or at the end of the page. Nevertheless, entire responses should be analyzed since it can be useful for other purposes such as inspection of other useful comments and hidden fields. Sometimes, web developers may not sufficiently obscure the information about the frameworks or components used. It is still possible to stumble upon something like this at the bottom of the page:

Figure 4.1.8-3: Banshee Bottom Page

Specific Files and Folders

There is another approach which greatly helps an attacker or tester to identify applications or components with high accuracy. Every web application component has its specific file and folder structure on the server. It has been noted that one can see the specific path from the HTML page source but sometimes they are not explicitly presented there and may still reside on the server.

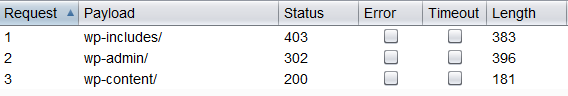

In order to uncover them, a technique known as forced browsing or “dirbusting” is used. Dirbusting is brute forcing a target with known folder and filenames and monitoring HTTP-responses to enumerate server content. This information can be used both for finding default files and attacking them, and for fingerprinting the web application. Dirbusting can be done in several ways, the example below shows a successful dirbusting attack against a WordPress-powered target with the help of defined list and intruder functionality of Burp Suite.

Figure 4.1.8-4: Dirbusting with Burp

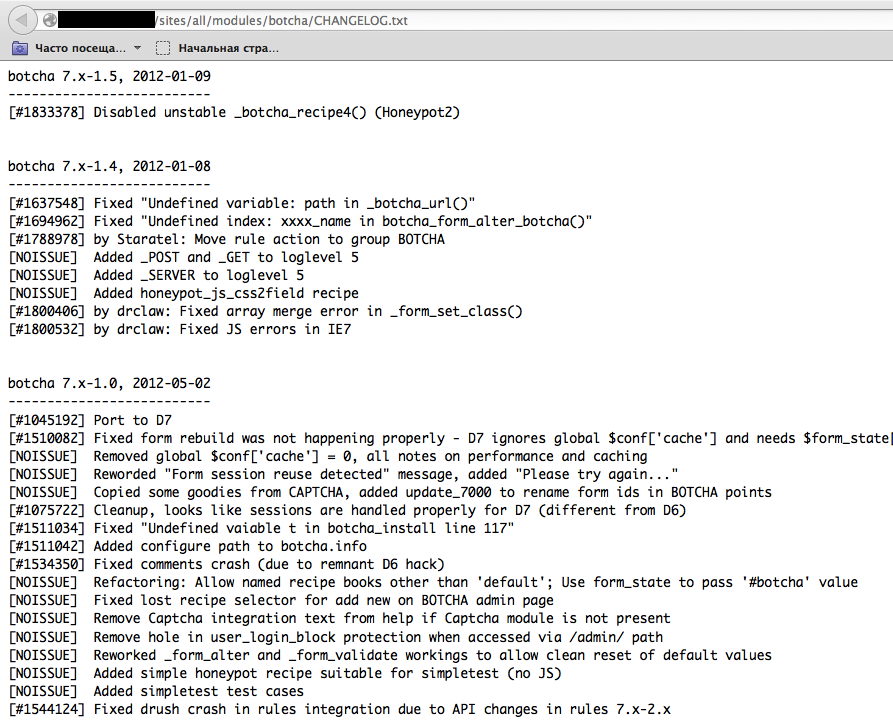

We can see that for some WordPress-specific folders (for instance, /wp-includes/, /wp-admin/ and /wp-content/) HTTP responses are 403 (Forbidden), 302 (Found, redirection to wp-login.php), and 200 (OK) respectively. This is a good indicator that the target is WordPress powered. The same way it is possible to dirbust different application plugin folders and their versions. In the screenshot below one can see a typical CHANGELOG file of a Drupal plugin, which provides information on the application being used and discloses a vulnerable plugin version.

Figure 4.1.8-5: Drupal Botcha Disclosure

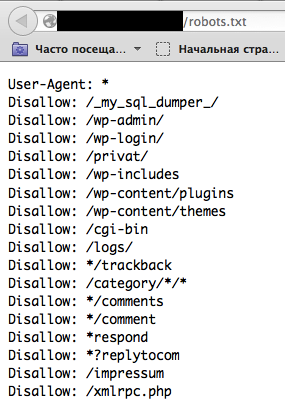

Tip: before starting with dirbusting, check the robots.txt file first. Sometimes application specific folders and other sensitive information can be found there as well. An example of such a robots.txt file is presented on a screenshot below.

Figure 4.1.8-6: Robots Info Disclosure

Specific files and folders are different for each specific application. If the identified application or component is Open Source there may be value in setting up a temporary installation during penetration tests in order to gain a better understanding of what infrastructure or functionality is presented, and what files might be left on the server. However, several useful file lists already exist; one notable example is the FuzzDB wordlists of predictable files/folders.

File Extensions

URLs may include file extensions that can also help identify the web platform or technology.

For example, the OWASP wiki used PHP:

https://wiki.owasp.org/index.php?title=Fingerprint_Web_Application_Framework&action=edit§ion=4

Here are some common web file extensions and associated technologies:

.php– PHP.aspx– Microsoft ASP.NET.jsp– Java Server Pages

Error Messages

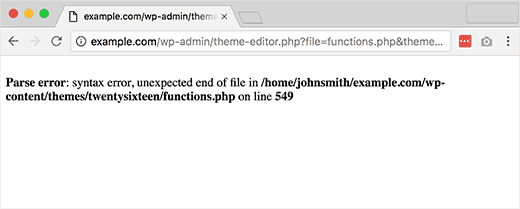

As can be seen in the following screenshot the listed file system path points to use of WordPress (wp-content). Also, testers should be aware that WordPress is PHP-based (functions.php).

Figure 4.1.8-7: WordPress Parse Error

Common Identifiers

Cookies

| Framework | Cookie name |

|---|---|

| Zope | zope3 |

| CakePHP | cakephp |

| Kohana | kohanasession |

| Laravel | laravel_session |

| phpBB | phpbb3_ |

| WordPress | wp-settings |

| 1C-Bitrix | BITRIX_ |

| AMPcms | AMP |

| Django CMS | django |

| DotNetNuke | DotNetNukeAnonymous |

| e107 | e107_tz |

| EPiServer | EPiTrace, EPiServer |

| Graffiti CMS | graffitibot |

| Hotaru CMS | hotaru_mobile |

| ImpressCMS | ICMSession |

| Indico | MAKACSESSION |

| InstantCMS | InstantCMS[logdate] |

| Kentico CMS | CMSPreferredCulture |

| MODx | SN4[12symb] |

| TYPO3 | fe_typo_user |

| Dynamicweb | Dynamicweb |

| LEPTON | lep[some_numeric_value]+sessionid |

| Wix | Domain=.wix.com |

| VIVVO | VivvoSessionId |

| Tiny File Manager | filemanager |

| Zenphoto | zenphoto_auth |

HTML Source Code

| Application | Keyword |

|---|---|

| WordPress | <meta name="generator" content="WordPress 3.9.2" /> |

| phpBB | <body id="phpbb" |

| Mediawiki | <meta name="generator" content="MediaWiki 1.21.9" /> |

| Joomla | <meta name="generator" content="Joomla! - Open Source Content Management" /> |

| Drupal | <meta name="Generator" content="Drupal 7 (https://drupal.org)" /> |

| DotNetNuke | DNN Platform - [https://www.dnnsoftware.com](https://www.dnnsoftware.com) |

General Markers

%framework_name%powered bybuilt uponrunning

Specific Markers

| Framework | Keyword |

|---|---|

| Adobe ColdFusion | <!-- START headerTags.cfm |

| Microsoft ASP.NET | __VIEWSTATE |

| ZK | <!-- ZK |

| Business Catalyst | <!-- BC_OBNW --> |

| Indexhibit | ndxz-studio |

Remediation

While efforts can be made to use different cookie names (through changing configs), hiding or changing file/directory paths (through rewriting or source code changes), removing known headers, etc., such efforts boil down to “security through obscurity”. System owners/administrators should recognize that such efforts only slow down the most rudimentary adversaries. The time and effort might be better spent on increasing stakeholder awareness and maintaining solutions.

Tools

A list of general and well-known tools is presented below. There are also a lot of other utilities, as well as framework-based fingerprinting tools.

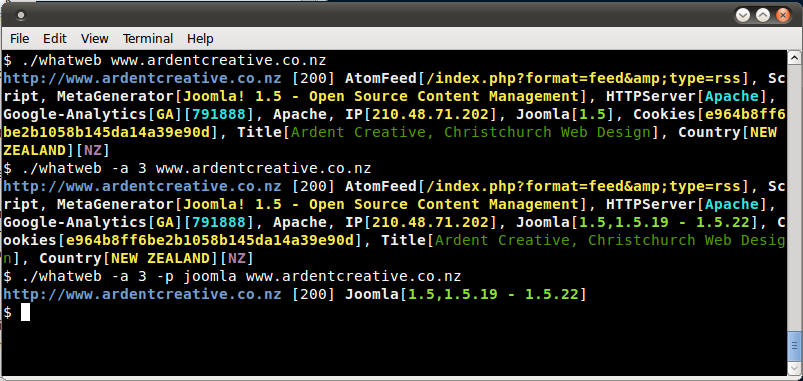

WhatWeb

Site: https://github.com/urbanadventurer/WhatWeb

WhatWeb is one of the best open source fingerprinting tools currently available on the market and is included in the default Kali Linux build. Language: Ruby Matches for fingerprinting are made with:

- Text strings (case sensitive)

- Regular expressions

- Google Hack Database queries (limited set of keywords)

- MD5 hashes

- URL recognition

- HTML tag patterns

- Custom ruby code for passive and aggressive operations

Sample output is presented on a screenshot below:

Figure 4.1.8-8: Whatweb Output sample

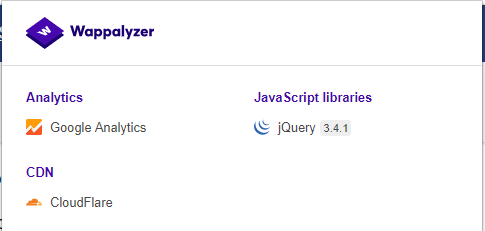

Wappalyzer

Site: https://www.wappalyzer.com/

Wappalyzer is available in multiple usage models, the most popular of which is likely the Firefox/Chrome extensions. They work largely on regular expression matching and don’t need anything beyond the page being loaded in a browser. It works completely at the browser level and gives results in the form of icons. Although sometimes it has false positives, this is very handy to have notion of what technologies were used to construct a target site immediately after browsing a page.

Sample output of a plug-in is presented on a screenshot below.

Figure 4.1.8-9: Wappalyzer Output for OWASP site